Bully Dogs Chapter 1: Dog Days for Frances Reed

Bully Dogs by Jacquie Ream:

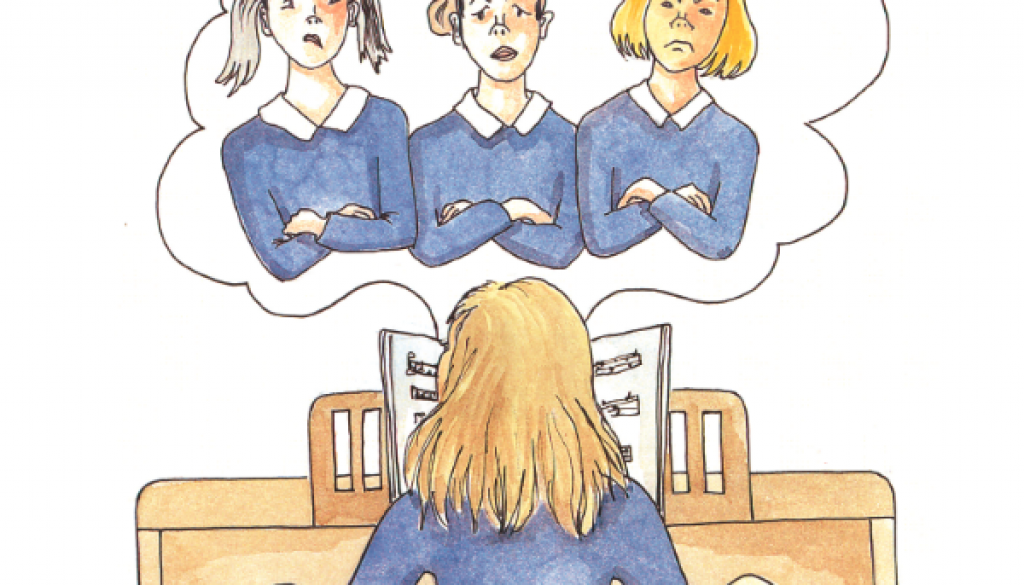

Faced with her neighbor’s three ferocious dogs, and a group of girls at school determined to put her down, Fran isn’t sure whether to stand up for herself or sit the tough times out. Fran’s chore-centric mother is no help! And one of her best friends, Annie, has begun hanging out with the bullies. When Fran sees that her school’s volleyball team won’t succeed unless the bullying ends, she realizes she’ll have to stand up for herself. But who should she face first: the vicious-looking dogs who chase her to school, or the girls who try to make her feel bad about being herself?

As Fran begins to discover her own strength and find her self-confidence, she sees bullies are like growling dogs who just won’t go away. And Bully Dogs proves that when it comes to bullies, their bark can be worse than their bite! Read for FREE on my blog>>

Bully Dogs Chapter 1: Dog Days for Frances Reed

My mom’s wrong. These are not my best years, and I seriously doubt I’ll look back upon my childhood as the happiest days of my life.

One way or the other, I wished I’d be dead by Friday, the morning of the girls’ sixth-grade volleyball team selection (that is, the Longest Hour in the Life of Frances Reed), or I knew I’d be suffering horribly after getting attacked by the bully dogs.

Maybe it would be better just to let the bully dogs eat me alive tomorrow morning. I’m getting plenty tired of running from the black Labrador, cocker spaniel, and golden retriever. Really, should I have to deal with three, big, dumb dogs that have taken a dislike to me, for what reason I have no idea? Old crotchety Mr. Wessenfeld used to walk them himself, but now he just lets them run loose.

I can’t help but wonder why things are the way they are, especially about adults and what they say or do or don’t bother to do at all. What gets me the most is all the preaching adults do about responsibility, and yet, no one has done anything about Mr. Wessenfeld, who lives four houses down across the street, letting his vicious mutts out every morning to do their number.

And boy, did they do a number on me! Snarling and yapping, they’d chase me down the end of the street, across Main Avenue, all the way to Saint Mary’s schoolyard. Some days, I just about didn’t make it to the chain-link gate that would separate me from them. And then didn’t I look just great, huffing and puffing, red-faced, and sweat running down my cheeks for the start of classes? I don’t have a lot in the looks department, not like some of the other girls in my class, and it really helped when I knew my scraggly brown bangs were plastered against my forehead. I’m sure I looked like a drowned mouse.

Annie, one of my best friends since second grade, told me I’m not ugly at all and understood how I felt, but I make her promise not to tell anyone, particularly Marcy, Sue, and Ursala. They would have had a field day if they’d known I’d run away from the bully dogs.

Not that “The Three Amigos” didn’t already give me a bad enough time and always had since kindergarten. Especially Marcy. We’d always been together in a small class. The biggest I remember was the combined fourth and fifth grades with twenty-one students, eleven boys and ten girls. Marcy and I were a bad combo, like a hyper cat and a snarling dog stuck together in the vet’s waiting room. We just didn’t mix well with each other, and the less she knew about me, the less she could telegraph all over Saint Mary’s barnyard with her mega-mouth. She was real quick with the nasty names that stuck, like calling me “Franny Fanny.” Most people, except my mom, call me Fran.

“Frances!”

“Yeah, Mom?” A quick glance at the clock and I knew that it was time to practice the piano and then the trumpet.

“Time to practice!”

“Just another five minutes, okay?”

“No!” Suddenly she was looming in my doorway. “That’s what you said at four-thirty after being on the phone twenty minutes giggling with Carol. Fifteen minutes on the trumpet, and thirty on the piano.”

“But I’m doing my math!” I pointed out reasonably enough. “And I only spoke with Carol for fifteen minutes.” I knew, because her mom has a timer by the phone. Carol is my very best friend, but she lives on the other end of town and goes to Saint Thomas, so we have to talk everyday so we know what’s happening with each other. She’s the only one that I don’t mind calling or talking to on the telephone. “I’m almost done, then I’ll go downstairs and practice. Okay?”

“No, now. You’ll have time to finish your homework before dinner. Go.” She dramatically threw her arm out, jabbing in the general direction of the stairs.

“All right, all right!” I put down my pencil and got up.

“Look,” her voice erupted like a volcano, “why don’t you just quit band and piano altogether? I hate these constant hassles with you.”

Actually, I like playing the trumpet and don’t really mind piano, though I’d been at it for five l-o-n-g years, practically half my life. Going over and over the same stuff bores me.

“So who’s hassling? I’m going right now.”

Her face was all pinched like she was mad. I didn’t know what made her so touchy, but I wished she’d relax. As she stood there glaring at me, I picked up the pencil that had bounced off the desk and rolled onto the floor and slid it in between pages of chapter six of The Sword in the Stone I’d been reading.

I always practiced the trumpet first, which I liked better, I suppose, because I was good for a first-year student. Miss Kray, our school bandmaster, said that if I kept improving as I had, I’d be first chair that year.

I was careful not to spend a lot of time cleaning my trumpet, or Mom would go nuts on me, reminding me it didn’t count for practice time. But I had to maintain my instrument, and I did what I had to do, then warmed up before “reviewing and renewing” band pieces for the week. After that I started the scales and triads on the piano.

Sometimes my dad would come downstairs to read the newspaper, and it’d make the time go faster. He thought he was giving me silent encouragement, but I knew he was only making sure I did my assignments. He’d always ask about my lessons, and I’d tell him Mrs. Nieman had given me another march or sonata that week.

“Good,” he’d say, “let me hear you play it like Sam Spade,” then laugh as he’d punch the front page in half and read on.

Sometimes I wish my older brother and sister were still at home, but most times I like being by myself with Mom and Dad. Mostly Dad. Mom and I get on each other’s nerves when we spend too much time together.

“Are you going to check my math tonight, Dad?” I asked as he settled into his chair.

He snapped the paper open and replied, “After dinner, okay?”

“Mom wouldn’t let me finish my math, and I’ve only got a couple of more problems to do. She made me come down here.”

“Play it again, Fran.” He waved his hand at me and buried his head into the financial section, but I saw him smiling when I started “When the Saints Come Marching In.”

“Can I read the comics before dinner?” I shouted above the crescendo finish.

“When you’re done!” he ended up roaring after the music had faded.

“All right, Dad, all right.”

By the time he was through with the paper, I was all done with practice and got a good start on the comics.

“What about your homework?” bellowed my mom from the top of the stairs.

“In a minute; almost done.” I had half a page to go, but it was no good telling her that it’d take me only another two minutes, max.

“Now, Frances.” With her hands on her hips and a mean scowl, she looked just like Henry the VIII, the old head-chopper.

“Just do it,” my father sighed, and I got up, finished with the last strip. My dad rattled the newspapers real loud as he collected the comics, loud enough so that I’d know he was the one picking them up, not me.

“Where’s the mail?” I heard Dad ask Mom.

“Frances brought it in for me,” Mom replied, then had to add, “If she put it down somewhere in her room, it’ll be lost in the black hole.”

I looked around my room. I knew where everything was. My shoes were beneath my uniform skirt and shirt, my science book was under my lunch sack in the corner where my stuffed animals kept watch over the defeated Redcoats, all lying dead from the last battle with the United States Army. Everything in its place, and a place for everything. Honestly, I can’t figure out why Mom kept on and on about what a mess the place was. Did it really matter? After all, I could find whatever I needed.

Dad walked in, making a big show of stepping over some books I had to return to the library, and frowned. “Franny, couldn’t you just throw out some of these papers?”

“Dad! Not that one. That’s my English, and it’s due tomorrow.” I snatched it away from him and handed him three letters and the junk mail with flyers that left a trail on my desk, across my bed, and on the floor. “I’ll pick those up later.”

But he’d already swooped down to gather them up. “No, it’s the least I can do for the cause,” he said then tweaked my nose before he left.

“Dinner! Wash up!” Mom’s voice echoed throughout the house. Just another three minutes and I’d be done with the last of the forty-two multiplication problems.

“Frances, please!”I finished the last sentence of the seventh chapter of The Sword in the Stone, dropped a book marker in it, and quickly did the last set . “Just one more minute,” I said. “One more and I’m done.”

As I sat down to the dinner table, Mom looked at me and said, “You didn’t wash up.”

“Oops, sorry. I didn’t have time.” I smiled at her, but she didn’t smile back.

“So how did school go today?” Dad asked as I mashed butter into the baked potato, the only good thing on my plate.

“It was okay,” I replied with a shrug, just to let them know that there is nothing worth telling about the sixth grade.

“No trouble with the gruesome-twosome?” He meant Marcy and Sue, who always gave me grief. Ursala just sort of hung out with them without ever really saying or doing much.

“Nah.” I looked up, and Mom was shooting daggers at me, so I took a bite of fish. “What’s for dessert?”

“Spinach soufflé.”

Sometimes I think my mom’s serious when she’s not. “Yuck!” That made her laugh, so I knew she was kidding. “That’s as bad as halibut.”

Wrong thing to say to her. “Eat it,” she snapped.

When I grow up, I don’t think Mom will ever come to my house and have dinner because I am not going to cook anything I don’t like to eat and that doesn’t leave much that she’ll want to eat.

“Bring me your math, and I’ll look it over while I’m having my strawberry shortcake.” Dad winked at me.

I choked down the last bit of fish and broccoli, washed the bad taste away with milk, then ran, and got my homework. All that exercise made me hungry. “Can I have lots of strawberries and whipping cream?”

“No, Frances,” of course, my mom said, “but I do have some more broccoli and fish if you want.”

“No, thanks, Mom.” But she brought in the beaters and bowl that she whipped the cream in and gave them to me. “All right! I’ll lick ‘em clean!”

“Franny.” Only my dad says Franny, and I knew he wasn’t pleased. “How is it you get the right answers on the hard ones and miss the easy problems?”

That’s how I am, I guess. “How many, Dad?” I hoped I could call it a day and get back to my book.

“Seven silly mistakes, my girl.” He handed me a pencil, eraser, and the paper. “I’ll recheck them after you’re done.”

I worked while Mom cleared the table and started the dishes. She was almost done loading the dishwasher when Dad went over the last set.

“Could you try being a littler neater, Fran?” he asked me for the umpteenth time.“I thought it looked pretty good.” And I looked again at the seven rows of six problems.

“You might erase instead of crossing out,” is all he said as he gave me back my paper.

“Sure, Dad.” I kissed him on the cheek and headed for my room.

“Frances!” Mothers have fantastic timing. I put down my book and waited. “Take out the garbage.”

“Right.” My mother the chore-master. I slid the empty wastebasket next to her as she swept the floor. I was almost out of there when she nabbed me again.

“Honey,” she leaned on the broom, “please put a liner in it for me.”

“Then can I read for a while?” I inquired sweetly.

“No, dear, it’s bath time.” She waited with exaggerated patience for me to punch down the plastic bag into the garbage can. “And please, no books in the bath tub.”

“Ah, Mom!” But I could see she wasn’t going to give an inch. Shower people do not understand the necessity of relaxing in the tub with a good book after a long day. I am not going to have even one shower in my house when I grow up.

“And wash your hair.”

“Anything else?”

“Brush and floss your teeth,” she said with a smile the Devil would have appreciated.

Well, she sure made short work of my favorite pastime. If I was lucky, she’d be doing the crossword puzzle and forget to watch the clock, and I’d get another chapter in before lights out.

I heard her footsteps coming down the hall, nine-o-five. Just this last half of a page and…

“Mark it, Frances.” Mom stood beside my bed, waiting.

But I was done before she plucked the book away from me and laid it on my desk. “Good night,” she said, shaking her head and rolling her eyes up in a look of mock despair as she brushed the drippy hair from my eyes. “Sweet dreams and don’t let the bedbugs bite.”

I gave her a kiss for a kiss, a hug for a hug. “Love you,” she whispered as she turned out the lights. “Aren’t you glad tomorrow’s Friday?” She closed the door, probably smiling to herself.

My heart sank.

Friday.